Jenna Starborn

Jenna Starborn Troubled Waters

Troubled Waters The Thirteenth House

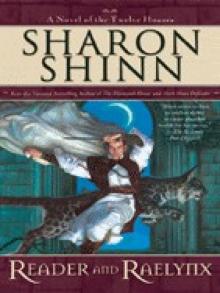

The Thirteenth House Reader and Raelynx

Reader and Raelynx Angel-Seeker

Angel-Seeker Archangel

Archangel Jeweled Fire

Jeweled Fire Nocturne

Nocturne The Shape-Changer's Wife

The Shape-Changer's Wife Still Life With Shape-Shifter

Still Life With Shape-Shifter Quatrain

Quatrain Fortune and Fate

Fortune and Fate Angelica

Angelica Summers at Castle Auburn

Summers at Castle Auburn Echo in Amethyst

Echo in Amethyst The Turning Season

The Turning Season Mystic and Rider

Mystic and Rider Heart of Gold

Heart of Gold The Shape of Desire

The Shape of Desire Echo in Onyx

Echo in Onyx Royal Airs

Royal Airs Gateway

Gateway The Safe-Keeper's Secret

The Safe-Keeper's Secret Wrapt in Crystal

Wrapt in Crystal Unquiet Land

Unquiet Land Jovah's Angel

Jovah's Angel Dark Moon Defender (Twelve Houses)

Dark Moon Defender (Twelve Houses) Mystic and Rider (Twelve Houses)

Mystic and Rider (Twelve Houses) Fortune and Fate (Twelve Houses)

Fortune and Fate (Twelve Houses) Reader and Raelynx (Twelve Houses)

Reader and Raelynx (Twelve Houses)